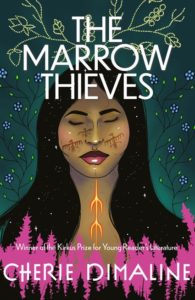

The book’s coming-of-age narrative, most notably Frenchie’s budding romance with rebellious and gutsy Rose, adds elements of tenderness and hope.

“The skeletons of the green trees curved under the elegant weight of the snow, bowing and twisting like ribbons in the wind,” she writes, providing a beautiful undercurrent to a world that seems to have been damaged beyond repair.

Though the novel tackles some heavy subject matter, The Marrow Thieves feels lighter as a result of Dimaline’s graceful, almost fragile, prose. Together, the ad hoc family attempts to protect the group’s oldest and youngest members from harm. Led by Miigwans – who lost his husband, Isaac, to recruiters – the group is forced to survive on limited resources, hunting with bows and arrows and guns, searching for drinkable water that hasn’t been poisoned, and building hidden camps. Like most Indigenous characters in The Marrow Thieves, Frenchie finds himself nomadic and alone, isolated from his community and family, including his brother, Mitch, who let himself be captured by recruiters so Frenchie could escape.Īn archetypal reluctant hero of the type that is familiar in dystopian YA novels, Frenchie forms a family unit with eight other Indigenous nomads, each of whom carries the weight of his or her own trauma. Indigenous leaders have attempted to negotiate with governors in the capital, but working with the government has failed. Set against a chaotic backdrop of torrential rain, food scarcity, and raccoons the size of huskies, The Marrow Thieves centres on Frenchie, a teenager on the run from government “recruiters.” Employed by the government of Canada’s Department of Oneirology, the recruiters forcibly take Inuit, Métis, and First Nations peoples to marrow-harvesting factories modelled after residential schools. Millions of people have lost their lives, and those who remain have endured trauma that has led to their inability to dream - with the exception of North America’s Indigenous peoples, who carry dreams in webs woven into their bone marrow.

Cities have crumbled from the coastlines, “breaking off like crust,” and hurricanes, earthquakes, and tsunamis have wiped out entire communities. In the latest YA novel by Métis writer and editor Cherie Dimaline, the world has been ravaged by global warming.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)